Good thing it’s still there! The steering wheel, I mean. Perhaps it’s the last bastion of the great tradition of the automobile industry, always ready to exploit the march of technology, in the sense that, well, almost everything else has changed about cars.

Let’s think about it, yielding a little to the seductive charm of nostalgia. Who still remembers those crank handles for win- ding down your windows on a hot summer day? And is it not true that the growing po- pularity of automatic transmissions has stolen away the thrill of the gearshift, that pleasurable jolt from second to third? And what happened to the clutch pedal? Today, many models even have windscreen wipers that start automatically at the first drop of rain …

Heavens above, this isn’t about opposing progress. And yet, fortunately, thank goodness, we’ve still got the steering wheel. It’s there, albeit in its sophisticated modernity, as if to represent an extreme physical connection between the human being and the mechanical means. Even in autonomous ‘driverless’ cars, driven by software and sensors, our beloved wheel remains, resists and survives.

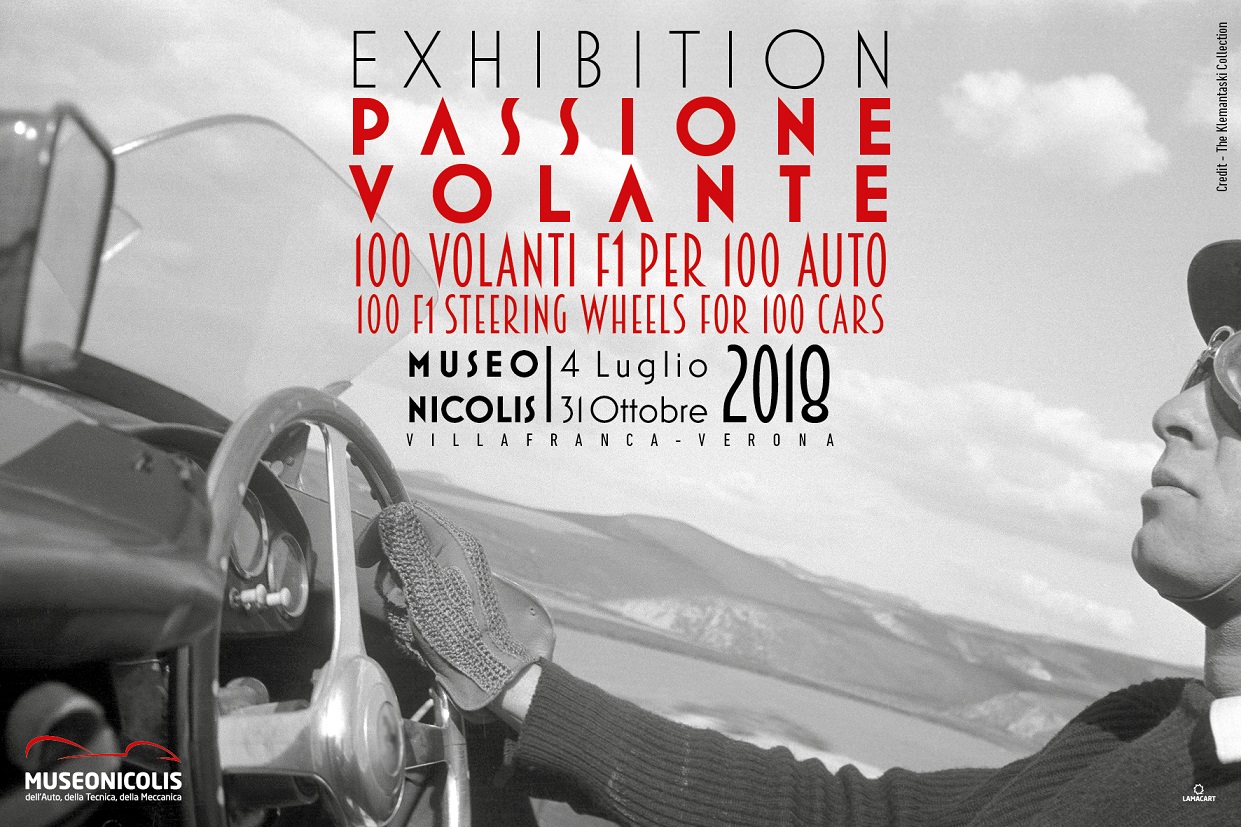

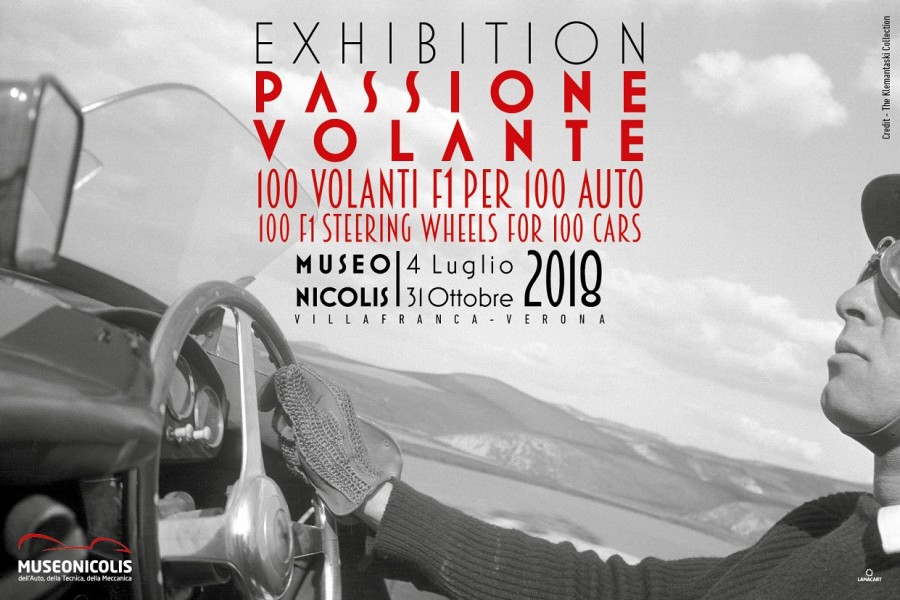

It is no coincidence, then, that the Nicolis Museum, a treasure trove of passion and culture (with over two hundred vintage cars, one hundred and five motorcycles, one hundred and twenty bicycles, five hundred cameras and one hundred typewriters), has chosen to dedicate an exhibition space to that most faithful friend of man and driver, above all that driver seeking a journey of emotions, memories, adventures and mysteries yet to be unveiled.

[‘On and on / there is a man behind the wheel / he has two eyes that he looks like a devil …’] (Francesco De Gregori).

Table of Contents

It was all already written

At the dawn of the twentieth century, in the age of extremes, the prophet of futurism, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, wrote in his ‘Manifesto’ some words that, for the Nicolis Museum’s exhibition, might fit perfectly as a message, a slogan or a symbol of the project: ‘We intend to hymn man at the steering wheel, the ideal axis of which intersects the earth, itself hurled ahead in its own race along the path of its orbit.’

From Marinetti, the futurist, to De Gregori, the singer-songwriter, a subtle thread guides us through time. The Wheel, let us capitalize it too, has become a symbol and a metaphor. Indeed, ‘the man behind the wheel’ is often used to describe a politician leading a nation, a popular industrialist or successful football coach.

The Wheel, in short, is a symptom of responsibility. Knowing how to handle it, in just the right way, is a sign of authority, of awareness, and a testimony of maturity. After all, turned on its head, what was meant by the motto (sexist, it goes without saying) of ‘Woman driving, peril thriving’? Was it not, even in a vulgarly improper way, a way for popular (impoverished) culture to reaffirm the absolute value of the steering wheel?

Who knows if he thought of all this the legendary Karl Benz, when, in 1886, he built his Velocipede (that can be admired at the Nicolis Museum), a pioneering object, which had a kind of rudder hooked to the front wheel. Perhaps Benz had thought of Ulysses, needing a helmsman to reach the frightening speed of ten miles per hour!

And yet, it was all already written, as you can see from the audacious experiments along the Nicolis Museum’s itinerary, from 1900’s Locomobile, with bar steering, to 1803’s Oldsmobile, controlled by a ox-tail lever.

Marinetti understood this: the ideal axis was to be the steering wheel that would catapult man into the esoteric dimension of the future.

‘I put my life in the hands of the wheel in every race. It’s like a tiny guardian angel for me’ – Juan Manuel Fangio, five times Formula One World Champion.

The hand of Teresa ( and James Bond)

Yeah, Fangio. The Champion of the Pampas, the record-holder of five world championships, which only a certain Michael Schumacher was able to beat. But a journey through the treasures of the Nicolis Museum will helps us, through Fangio himself, to overcome that already evoked prejudice, that bothersome juxtaposition between a woman behind the wheel and constant danger.

It is not necessary to be devoted to the suggestion of political correctness. Just look at the Maserati 250 F, the legendary single-seater of the last century’s fifties. With that car, Fangio literally flew. But the hands of Maria Teresa De Filippis also rested on that steering wheel, a daring young lady who was a racing driver by trade, and did so without having anything to envy of her male colleagues. We owe her the final liquidation of a hateful prejudice. Teresina, as her contemporaries affectionately called her, was a true pioneer, and, after all, with a bit of imagination, we might even suppose that her exploits suggested to the writers of 007 that particular scene on the Cote d’Azur, on the Corniche, where we see a James Bond, played by the excellent Pierce Brosnan aboard his famous Aston Martin, accept defeat from a woman driving a Ferrari.

‘At the end of every edition of the Monte Carlo Grand Prix, with all those bends and all those gear shifts, my hands were sore, and I would have paid out of my own pocket to have a softer steering wheel!’ – Clay Regazzoni

The Courage of Arturo

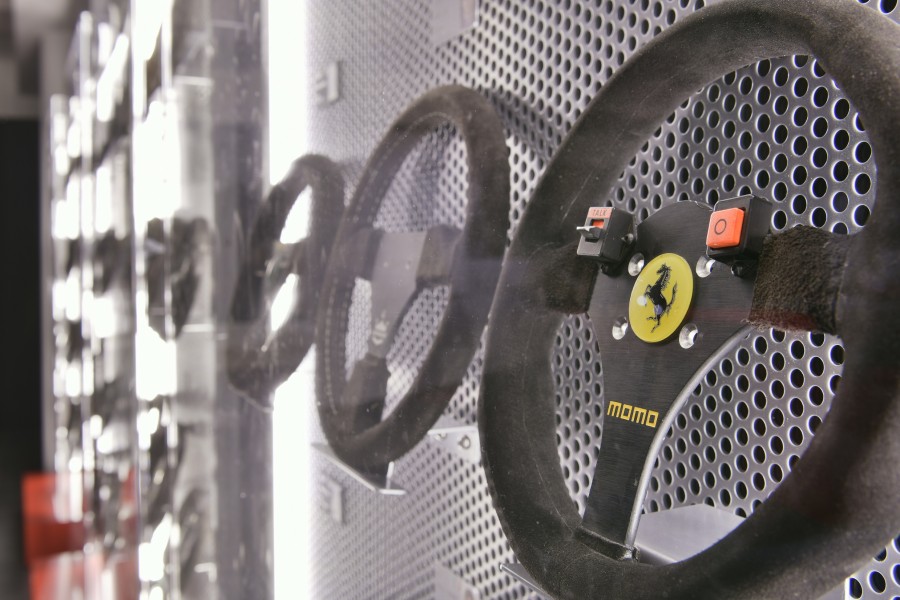

Of course, even in the field of the steering wheel, technological development has left its mark, realizing the dream of Clay Regazzoni, Ferrari’s ace of the seventies. The creations of Momo, Personal and Fondmetal have had a profound influence on the qualities of the object, coming, indeed, from the world of racing cars (but not only, sure).

The Nicolis Museum exhibition, with over one hundred pieces on display, many of them of Formula One cars, others of GTs, charmingly re-enacts that relationship between hands and the car, hands that transmit the impulses of the brain to the machine, in a contamination between gesture and thought.

That’s right, that noble thought that crossed the mind of Arturo Merzario on a summer’s Sunday at the Nurburgring in 1976, when an intersection of destinies culminated in a dramatic collision of emotions. Merzario, an excellent racing driver of the Italian school, had been turned away by Ferrari to give way to Niki Lauda. Indeed, there was no love lost between the two, as befitted their track rivalry.

At one point in that German Grand Prix, the Austrian champion’s Rossa crashed into the Ring’s rocks and caught fire. Lauda, still conscious, was not able to get out of the cockpit. He would have died horribly in the flames, poor Niki, if Merzario himself, arriving in the area with his car, had not made the decision that saved a life.

Arturo stopped, yanked off his steering wheel, rushed into the fire and saved Lauda from a cruel end. That yanked steering wheel opens the Nicolis Museum’s exhibition. It’s a piece of history, history that reminds us of how motoring racing is more, much more than a simple contest at two hundred miles per hour.

‘When I put my hands on the wheel, I enter a different dimension. I realize I’m going to do what I’ve always dreamed of doing’ – Ayrton Senna

Give me a lever and I will move the world

Today in the new millennium, the car we have in the garage offers us a steering wheel that certainly is not just for steering the wheels. It’s as if we had none other than touch-enabled computer, with software to make us masters of our dominion. There are buttons, and more buttons, levers, and more levers. We can change radio station, raise or lower the volume, answer a call, adjust the air conditioning, and more, all without ever taking our hands off the instrument that binds us instinctively to the journey we are set on.

‘Give me a lever and I will move the world’, it seems the legendary Archimedes once said, not necessarily having the automobile in mind, or perhaps yes? Have these levers and bars not irreversibly modified the way we drive, whether we are racing or not?

In the Grand Prix universe, the great revolution hypothesized by the engineer Archimedes was introduced by Ferrari. It was the year 1989, and, in Brazil, on the Jacarepaguá circuit, in a neighbourhood of Rio de Janeiro, the world championship was about to begin and La Rossa was presenting its F1-89 model. Designed by the British designer John Barnard, it used an old idea from Mauro Forghieri, who, for a quarter of a century, partnered the ‘Drake of Maranello’ as head of the racing department.

Forghieri had prepared a car without a gearstick; in order to change gear, the driver could simply use two tabs located behind the steering wheel. The brilliant solution was put on ice by Gilles Villeneuve, since the legendary Canadian champion didn’t think the time was ripe, in 1982, for such a revolution.

However, in 1989, the future was knocking at the door and that ‘alien’ steering wheel, Archimedes’ wheel, was ready to make its impact on reality. The Nicolis Museum has it, that magical artefact, coming from the Ferrari of Nigel Mansell, who, against every prediction, triumphed at the debut on a sunny Brazilian Sunday.

Perhaps no-one had ever explained it to Mansell, the pyrotechnic warrior of the track, that there was the genius of Archimedes behind his win.

Alberto Sordi and the Smugglers

Ah, how many fragments of memory add up and overlap, how many moments of scattered experiences turn around the steering wheel?! If only the steering wheel of 1938’s Lancia Astura Sport MM could speak, for example, I’m sure it would have lots of happy stories to tell. But also unhappy stories. Built for the ace Gigi Villoresi, the car, after a thousand good adventures, ended up in the hands (with hands also being, in their way, a mirror of the soul) of Swiss smugglers, who packed it with luxury watches for a very profitable trafficking. Then it disappeared and lay sequestered in a warehouse, from where Luciano Nicolis happily recovered it, giving it a new existence, saving the unique, never-to-be- replicated model from anonymity.

And how nice it would be if having a voice were the steering wheel of the 1960’s Maserati 3500 GT, aesthetically enhanced by the lines of Carrozzeria Vignale! The car that belongs to the history of great Italian cinema, because Dino Risi wanted it on the set of his masterpiece, ‘Una vita difficile’, a film sublimated by what was perhaps Alberto Sordi’s greatest interpretation.

And how many secrets must the steering wheel of 1963’s Ferrari GTE have? It was the first ‘2+2’ from the ‘Prancing Horse’, a gem that had created many problems at the design stage for those that had conceived it. In the end, however, the creature lived up to expectations, turning any remaining doubts into jubilation and applause.

If only Schumi could…

‚Steering Passion’, among many other pearls, offers a triple homage to Michael Schumacher, the seven-time Formula One World Champion.

Part of the museum tour are three of his steering wheels, dating back to the period when the German raced for Benetton.

Observing them up close, it is practically impossible not to shed a tear. Just looking at them takes you back to those perfect hands that knew how to do everything with them, in the glorious days that Schumi was a musician and conductor extracting from the steering wheel the very best sound, a clean melody, a perfect harmony.

Reflecting in the silence of emotion, the dream of a heart comes to you.

Eh, if only Schumi could come back and caress them, those three steering wheels

The Professor’s last

In 1993, Alain Prost won his fourth Formula One world title. The Frenchman had returned to racing after a year off, and had chosen to work with Williams Renault in his hunt for yet another championship consecration. The Nicolis Museum houses what was the last steering wheel of the Professor, as the former Ferrari driver was nicknamed, protagonist of a fascinating and dramatic rivalry with Ayrton Senna. When Prost finished the Australian Grand Prix of that 1993 season, he waited a moment before pulling the steering wheel from his single- seater. ‘I realized at that moment’, Alain would later say, ‘that one small gesture would bring a stop to a long period in my life. I had, in fact, decided to leave racing forever’

And Prost kept his word.

The Emperor’s Driver

Ukyo Katayama has not entered the pantheon of the great drivers that have made the history of Formula One. Yet this Japanese driver felt his hands shake, not in the cockpit of the Tyrell (two of its steering wheels, dating from 1994 and 1995, are present in the exhibition), but from the task entrusted to him, on the Suzuka Circuit, of driving round the descendants of the Japanese imperial family, on their visit to the Honda track. It seems that the steering wheel is still soaked with sweat!

Following his father’s footsteps

Motor racing has its own dynastic tradition, since the remote and glorious era of Antonio and Ciccio Ascari, father and son united by a tragic destiny, both victims of the passion for speed. In more recent times, illustrious heirs such as Jacques Villeneuve and Nico Rosberg have ascended to the throne reserved for the world champion of Formula One. However, the first not only to follow in the footsteps of his father, but also to surpass him in his endeavours, with Williams in 1996, was the Brit Damon Hill, scion of the legendary Graham. Naturally, Hill Junior’s steering wheel is part of the Nicolis Museum’s exhibition.

The wheel of Il Duce

1941’s Fiat 1500C Bertone, present in the museum, has a particular historical value. The car, built when Italy was already involved in the tragedy of the Second World War, was one of the last industrial products of the fascist era before the catastrophe of 8th September 1943. Benito Mussolini, who had wanted to drive it, probably no longer had any way of touching a steering wheel in his capacity as Il Duce and Marshal of the Empire.

Monica’s whell

The Delahaye 135 M was a car that anticipated, even in 1939, the innovation of the futuristic sequential gearbox, and was an electromagnetic jewel of the visionary intuition of its French designers. The model returned to prominence in 2008, when Monica Bellucci took its wheel in a film with Luca Zingaretti (the well-known Commissioner Montalbano of the Italian state Broadcaster’s television series) called ‘Wild Blood’ by the director Marco Tullio Giordana.

To catch a thief

Legend has it that someone tried to steal, as a precious relic, the steering wheel that Jean Alesi used in 1991 in Montreal, Canada, to win the only Grand Prix of his wonderful yet unfortunate career. An idol of Ferrari fans for five seasons, the Frenchman of Sicilian origins did not get what he deserved for his talent and his courage. But his steering wheel is still here and on display at the Nicolis Museum, and there’s no need To Catch a Thief, the film that made such a unique driver as Grace Kelly all the more famous

The great train robber

Few people know that Lotus, the legendary British Formula One racing team, entrusted the choice of the shape of its cars’ steering wheels to its founder, the colourful Colin Chapman. A brilliant racing enthusiast, Chapman had also won the esteem of Enzo Ferrari, his great Italian rival. He died, they say, in 1982, but some would have it that he disappeared to finally enjoy the fruits of the Great Train Robbery they believe he participated in during the 1960s. Metropolitan legends, while it is true that his creativity is dedicated to the two steering wheels used by Mika Hakkinen when he ran for the Lotus brand, between 1991 and 1992.

Ronnie’s friend

Michele Alboreto, the last Italian driver chosen directly by Enzo Ferrari for his single-seaters, is remembered in the Nicolis Museum’s exhibition with as many as four steering wheel specimens. The Lombardy driver had grown up with the legend of Ronnie Peterson, an extremely talented Swedish driver, who never became world champion but was well respected for his great courage. Alboreto had studied the way his idol Ronnie held the steering wheel, carefully copying his manner

Dear Elio

On 15th August 1982, there was an incredible end to the Austrian Grand Prix on the Zeltweg track. Two of the race cars crossed the finish line in perfect harmony. Only the photo finish could reveal the question of centimeters translated into thousandths of a second that divided them. The victory was assigned to the Italian Elio De Angelis’ Lotus, and stolen from the Finn Keke Rosberg’s Williams. The steering wheel from that victory of the Roman driver, killed in an accident in 1986, during private testing with the Brabham on the Castellet circuit in France, could not be missing from the Nicolis Museum’s exhibition.

Dustin & Duetto

Among the many Alfa Gran Turismo steering wheels on display at the Nicolis Museum, it is possible to grasp the inspiration that led to the creation of the front inside of the famous Duetto. The Biscione’s car remained in collective memory also thanks to Dustin Hoffman, who wanted that model for a film, ‘The Graduate’, which was destined for great success both in commercial terms and as a symbolic value of an era of social and cultural change.

Dopo Ayrton

On 1st May 1994, Formula One lost an absolute legend, when a terrible crash at the Imola circuit cost the life of Ayrton Senna. To replace the Brazilian champion on track, the Williams team chose a promising Scottish driver, David Coulthard. On show is the steering wheel used by the Brit in his debut

The roar of the lion

After a pursuit that had lasted for over ten years, Nigel Mansell finally graduated as world champion in 1992. He mathematically conquered the title with a Renault-powered Williams on the Hungaroring track at the gates of Budapest. The Nicolis Museum’s exhibition displays the steering wheel that allowed ‘The Lion of the Isle of Man’ to realize his long sought after dream.

Ciao Ciccio!

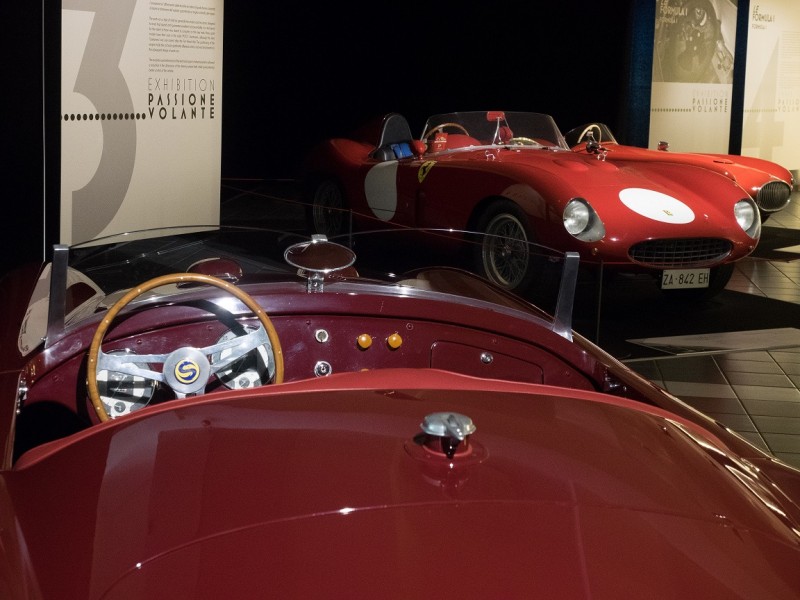

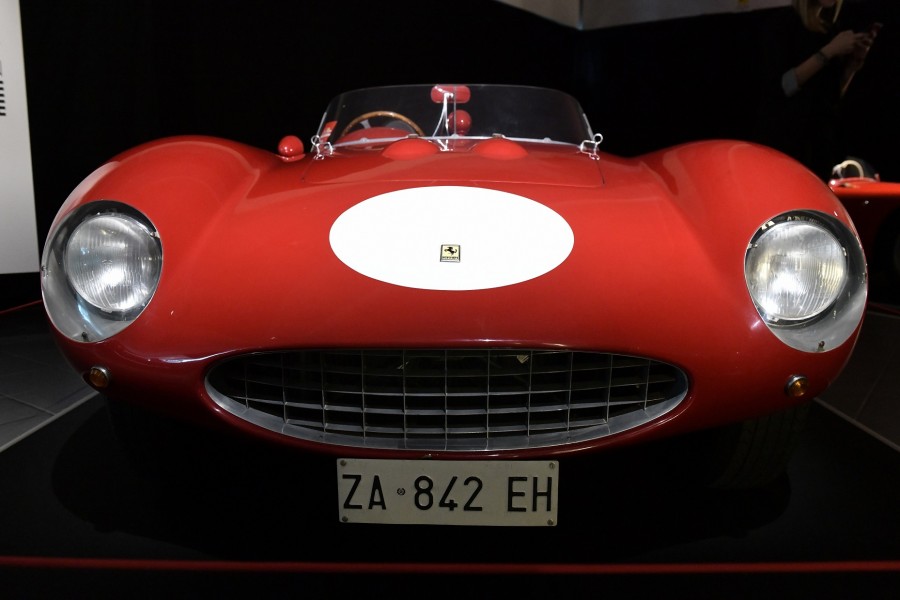

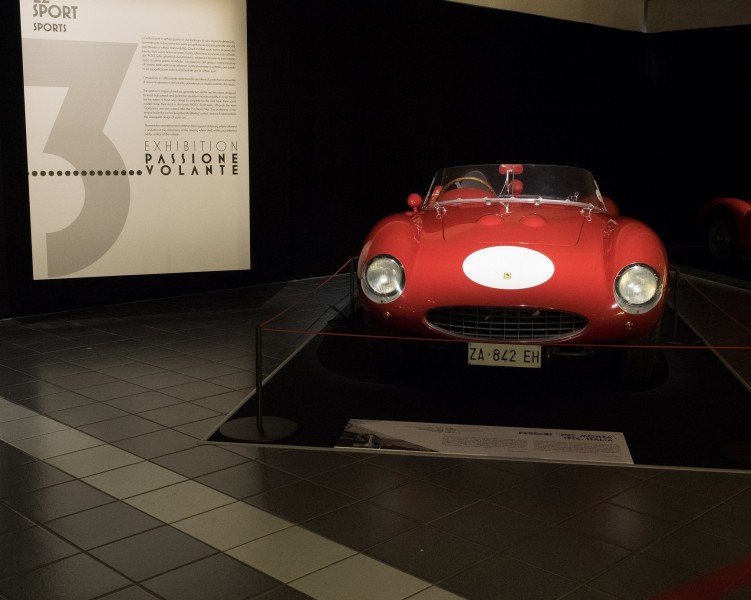

The Ferrari 750 Monza was one of the highest expressions of Italian engineering applied to racing during the fifties. It is also the last car Ciccio Ascari climbed into. The two-time Formula One World Champion died in a mysterious accident, right on the Monza circuit, during a series of private tests.

Grand Prix

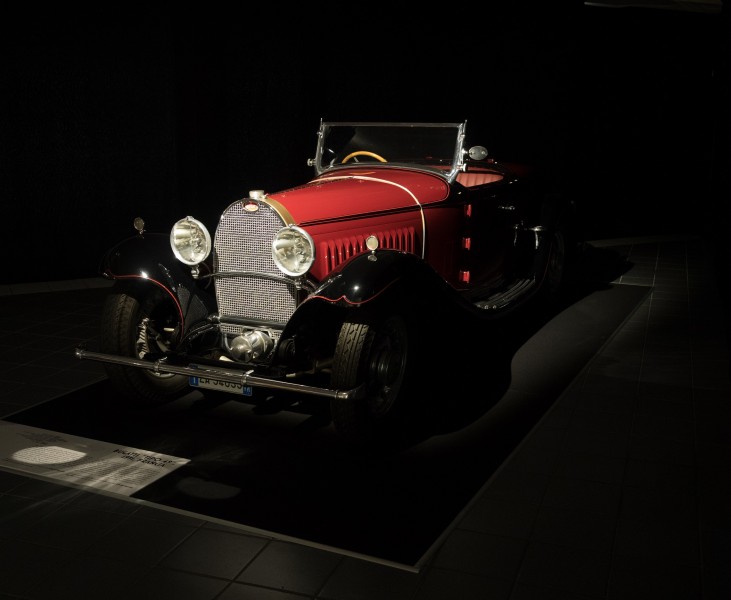

Not all attempts to transform the emotions of racing into great cinema have been hailed a success. Perhaps it is just too difficult to transfer this reality to the vertical plane of artistic fiction. Nonetheless, ‘Grand Prix’, a film from 1966, is still considered to be the most successful attempt yet. From that film the Nicolis has 1931’s Bugatti Type 49, the last model designed by the founder Ettore

Umberto’s Fiat

Few are aware of this, and yet Umberto Agnelli, brother of ‘The Lawyer’ Gianni and president of Fiat until his death in 2004, had had some fun in his youth as a driver in several races. His favourite models came from the Turin factory and were reworked in Modena by the Stanguellini family, such as 1948’s Fiat 1100 Sport Motto, also present at the Mille Miglia of that year.

The Great Beauty

Better just say it. It is almost impossible to choose from the many cars gleaming in front of your eyes as works of art under the roof of the Nicolis Museum. The Great Beauty of mechanics has all the charm of an enchantment.

But let’s try, for fun and for love, to select ten of these roaring masterpieces, matching each car with a well-known figure, in an interweaving of sensations that mix history, culture, tradition and passion.

Ready? Get set. Go!

- Ford Thunderbird Convertibile. 1955. Ideal driver: Bruce Springsteen, the minstrel of rock, the man who was ‘Born to Run’. It’s all too easy to imagine him at the wheel of a Thun- derbird in pursuit of freedom among the many contradictions of an America we will continue to love and hate thanks to his wonderful songs.

- Itala Tipo 50 25/35 hp Torpedo. 1920. Ideal driver: Enzo Ferrari.Don’t be surprised by this pairing of vehicle and driver. Immediately after the cruel vicissitudes of the First World War, the future Drake of Maranello wanted to be a racing champion and was fascinated by Italian technological development of the time. And this Itala had everything to please him.

- Lancia Fulvia 1300 S Coupè. 1976. Ideal driver: Mogol. Known to the registry office as Giulio Rapetti, Mogol wrote the lyrics of the most beautiful Italian songs of the twentieth century, from ‘Emozioni’ and ‘Il mio canto libero’ to ‘L’Emozione non ha voce’. And to him we also owe the verses of ‘Sì viaggiare’, the road anthem of the legendary Lucio Battisti. It would seem as if ‘that great genius of my friend’, the protagonist of the song, ‘with his hands soiled with oil’, had been working on just this model of Lancia.

- De Lorean Dmc 12 coupè. 1981. Ideal driver: Michael Fox. There are films that remain in collective memory beyond their real artistic value. This was the case for the ‘Back to the Future’ series, in which the De Lorean allowed the American actor Michael J. Fox to travel through time. It was precisely the DMC 12 model. And what if it were not just a load of special effects?

- Matra Bagheera 2 Coupè. 1974. Ideal driver: Alain Delon. A French gem, the perfect car for a night out on the roads of the French Riviera under a ceiling of stars. We are in the seventies and Alain Delon, a handsome, brooding idol of generations of women, is racing to meet Romy Schneider for an unbridled triumph of carnal emotions.

- Maserati Indy 4900. 1973. Ideal driver:: Mario Andretti. The indestructible force of the Trident brand. Few remember, but only Maserati, among the Italian car makers, won the Indianapolis 500. It seems right then to entrust the steering wheel of this Indy 4900 to the Istrian Mario Andretti, the only Italian-born driver first under the checkered flag of the most famous oval circuit on the planet.

- Fiat 500 R. 1975. Ideal driver: Luca Cordero di Montezemolo. A re-edition of ‘The Way We Were’, a plunge into Italy’s black and white era, still capable of cultivating high hopes. In 1975, the young lawyer Montezemolo, then Ferrari’s sports director, used the 500 R to commute from his Modena house to the Maranello offices.

- Alfa Romeo RM La Zagato. 1925. Ideal driver: Benito Mussolini. Benito Legend has it that Il Duce was at the wheel of this car, near Rome, when another car dared overtake. The head of the government took it bad and ordered a fine on the reprobate. However, when he found out it was his favorite footballer, Fulvio Bernardini, he cancelled the order, and learnt to drive the La Zagato better.

- Aventure. Vettura a pedali. 1882. Ideal driver: Vincenzo Nibali. The design was alreadThe design was already there, the chassis, steering and handlebar of sorts too. Pending a real engine, it relied on pedal power. And who better to supply that power than the Sicilian winner of the Giro, the Tour and the Vuelta?

- Lamborghini Espada 400 Gt. Bertone Coupè. 1969. Ideal driver: Neil Armstrong. In 1969, when this creature came out of the Santa Agata Bolognese workshops, the first man set foot on the moon, his name Neil Later he became a member of Chrysler’s board of directors, contributing with his advice to the purchase of the Toro brand by the US company. The moon’s first man liked Lamborghinis a lot.

Leo Turrini

Inaugurazione, taglio del nastro