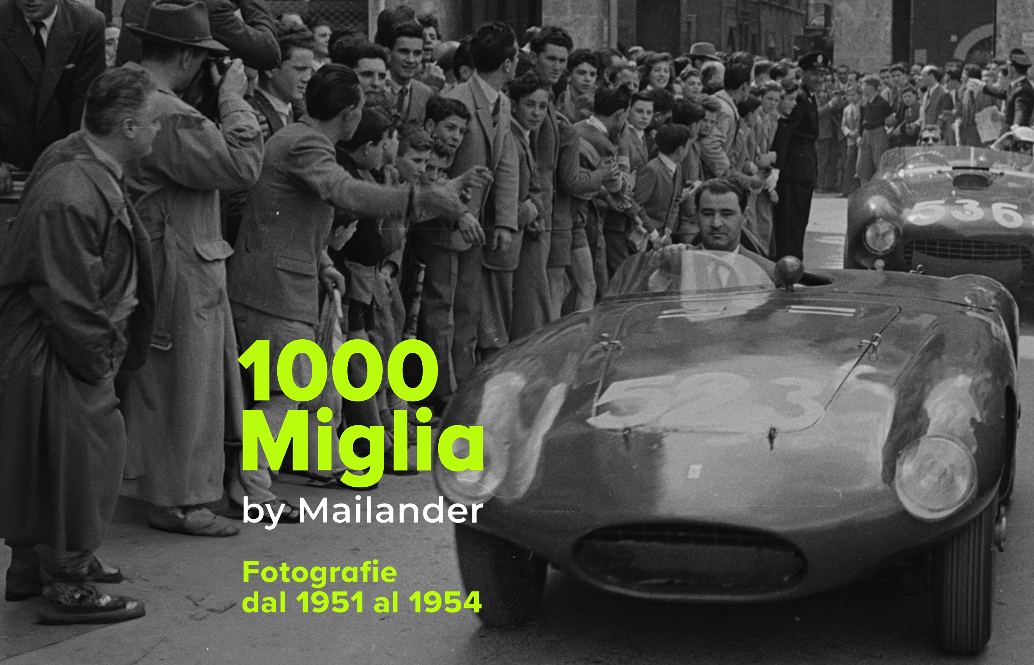

Mostra, 1000 Miglia by Mailander

Table of Contents

From 17 May to 13 October on show at the Museo Nicolis 12 photos preserved by the Revs Institute in Florida

The exhibition combines a selection of shots taken by Rodolfo Mailander, a great photographer of the 1950s motoring era.

It is the first fruit of a partnership between the Fondazione Gino Macaluso per l’Auto Storica and the four main car museums in Italy: Museo Nicolis in Villafranca di Verona, Museo Nazionale dell’Automobile in Turin, Museo Mille Miglia in Brescia, and Museo Fratelli Cozzi in Legnano.

At the Museo Nicolis, the focus is on the Marzotto brothers, sons of a family of industrialists from Valdagno. In the 1950s, they often participated in the 1000 Miglia, almost always in Ferraris. In 1953, Giannino Marzotto won the race for the second time in his life in a Ferrari 340 MM. Marzotto produced yarns and clothes, a peculiarity that allowed the brothers to distinguish themselves in the race also in terms of style: their modern elegance heralded an era of exuberance and optimism.

The Nicolis proposes a diffuse itinerary that sees on the ground floor the heart of the exhibition composed of twelve unpublished photos with the Marzotto brothers as their subjects in the Mille Miglia between 1951 and 1954. Welcoming the visitor is a Lancia Aurelia B20 celebrating its many victories: ‘And then, excuse me, how could anyone sleep knowing that in a while the Marzotto brothers would arrive, also from Veneto, “current accounts” people used to call them with a touch of irony. Giannino won two Mille Miglias in 1950 and 1953, always in Ferraris. But the brothers Vittorio and Paolo were also walking strong, and Umberto had demonstrated his courage at the Mille Miglia on 26 April 1953 in an Aurelia B20 paired with Gino Bronzoni. The year before, at the 1952 Mille Miglia, no fewer than four Aurelia B20s finished in the top ten.’

The exhibition criterion is exciting thanks to immersive 1950s-inspired set designs such as the Sports Bar, the Journalist’s Office, the Driver’s Office and the Photo Reporter. Also along the route are the Trophies won by legendary drivers such as Nuvolari and Ascari, the Vintage Workshop with Bugatti bench and numerous car models (about 20 out of 90 cars on display) that took part in the Mille Miglia, including the iconic Lancia Astura Mille Miglia of 1938 and the Fiat 1100 Sport Motto of 1948, unique examples that competed in the historic editions.

Like cinema and other art forms, ‘The Most Beautiful Race in the World’ expressed what Italy felt about itself. Mailander’s Leica lens thus became a window on a crucial passage in Italian history, allowing us to relive the rebirth of a nation’s great ambitions through what had ceased to be a simple motor race.

Content of the Exhibition at the Museo Nicolis

1. Giannino Marzotto’s Ferrari 212, known as ‘The Egg’, built by Paolo Fontana to a design by Sergio Reggiani, 1951

2. Paolo Marzotto and Marino Marini’s Ferrari 166 with bodywork by Touring, 1951

3. Vittorio Marzotto in his Ferrari 225 S spider with bodywork by Vignale, 1952

4. Giannino Marzotto and Marco Crosara in the Ferrari 340 MM spider, bodied by Vignale to a design by Giovanni Michelotti, 1953

5. Umberto Marzotto and Gino Bronzoni in the Lancia Aurelia B20 GT, 1953

6. Umberto Marzotto and Gino Bronzoni in the Lancia Aurelia B20 GT, 1953

7. Giannino Marzotto and Marco Crosara winning the 1000 Miglia in a Ferrari 340MM Spider in 1953

8. Vittorio Marzotto, alone at the 1000 Miglia in 1954; it was the first year that drivers could participate without a co-driver

9. Giannino Marzotto with his co-driver and sister-in-law Gina Tortima, 1954

10. Giannino Marzotto interviewed on the radio before the start, 1954

11. Paolo Marzotto (wearing sunglasses) climbs into his Ferrari 375 MM designed by Pininfarina, 1954

12. Vittorio Marzotto in his Ferrari 500 Mondial, designed by Sergio Scaglietti, 1954

The Context. Edited by Danilo Castellarin

The Mille Miglia: Everything was slow in 1950s Italy. There were many bicycles, many horses pulling carts, a few Vespas, and very few cars. Only the Mille Miglia ran fast, leaving Brescia in the middle of the night, arriving in Rome, and then returning to where it had started.

Night dream: The drivers were called ‘racers’ and the cars ‘racing cars’. The country would spend a sleepless night, huddling around the most difficult corners and setting up a few old chairs in front of the doorway to get a close look at the ‘Knights of Risk’.

Between champions and poor people: There were the champions like Ascari, Villoresi, Bonetto and nostalgia for the great Nuvolari who had left forever in the summer of 1953 after giving men and women the pride of being Italian, winning races all over the world. But they also raced dozens of anonymous people who wanted to live that dream at least once in their lives. – They would only arrive at dawn.

Valve radio: Television would only arrive in the homes of the lucky few in 1954. Everyone, however, had the valve radio that turned on softly, with a green light that looked like a magic eye and made you dream. «Maria, turn up the volume, I want to hear who’s leading the Mille Miglia», shouted grandpa hard of hearing as Cabianca’s Ferrari, the Veronese driver who was racing hard, sped by.

Aunt Olga’s Bianchi: Around midnight the children were pinching each other’s cheeks to stay awake. Mum and dad wanted to send them to bed, but they had heard from Aunt Olga, who had just arrived with the shiny, black Bianchi bike, that the most beautiful cars -the bright red ones like the Alfa, Maserati and Ferrari- would only arrive at dawn.

The Marzotto Brothers: And then, how could anyone sleep knowing that in a while the Marzotto brothers, also from Veneto, would arrive, ‘current accounts’ people called them with a touch of irony. Giannino had won two Mille Miglias, in 1950 and 1953, always in Ferrari. But the brothers Vittorio, Paolo and Umberto were also walking strong, and Umberto had demonstrated his courage at the Mille Miglia on 26 April 1953 in an Aurelia B20 paired with Gino Bronzoni. The year before, at the 1952 Mille Miglia, no fewer than four Aurelia B20s finished in the top ten.

Race reporting: Meanwhile, journalists were writing reports on Olivetti typewriters and then looking for a telephone to dictate the chronicle of the race to the editorial staff. There were no mobile phones, computers, or e-mail. Many took photos with flash and then sent the negatives to the newspaper, entrusting the films to the train conductors of the direttissimi, as today’s Frecciarossa trains are called. Hoping they would arrive at the finish line together with the winner…

Rodolfo ‘Rudy’ Mailander: The life of Rodolfo Mailander (1923-2008) is all about his passion for cars. He began photographing them when he was only 18 years old and was already a correspondent for important car magazines after the war, including the prestigious Automobil Revue and Auto Motor und Sport. From 1950 to 1955, Mailander used his Leica to capture the revival of racing in Europe with extraordinary clarity. His command of languages, technical expertise and first-hand knowledge of the protagonists of the time then led him to Stuttgart at Daimler-Benz (Mercedes), as director of external relations and the press office. In 1960, he moved to Turin to take on the role of director of international relations at Fiat; here he would work for almost 30 years, a good part of which as director of the presidency alongside Avvocato Giovanni Agnelli and Dr Umberto Agnelli.

The Revs Institute: The Revs Institute is a global non-profit resource for the community of historic car scholars. Its mission is to preserve the automobile as a tangible legacy and as a lens for understanding the past. The Institute is best known for its museum in Naples, Florida, where over 100 Miles Collier Collections cars are displayed. It also houses an archive with original documents and over 2 million photographs, a library with over 26,000 books and 200,000 periodicals related to automotive history, a teaching facility for the RevsEd continuing education program, and a workshop that keeps every car in the museum running. It also houses the Rodolfo Mailander Photograph Collection, of which it has digitised Mailander’s 30,869 negatives, making all the images available online in its Digital Library.